Written by Diana Yates

Illinois News Bureau

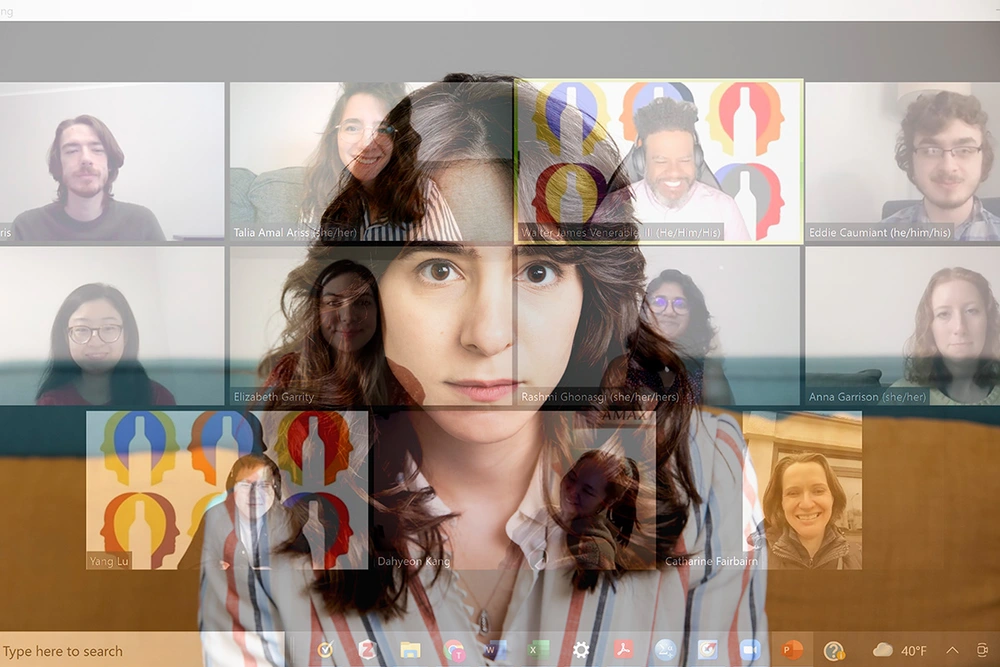

Photo Credit: Michelle Hassel

A new study finds that the more a person stares at themself while talking with a partner in an online chat, the more their mood degrades over the course of the conversation. Alcohol use appears to worsen the problem, the researchers found.

Reported in the journal Clinical Psychological Science, the findings point to a potentially problematic role of online meeting platforms in exacerbating psychological problems like anxiety and depression, the researchers said.

Watch a video about the research.

“We used eye-tracking technology to examine the relationship between mood, alcohol and attentional focus during virtual social interaction,” said Talia Ariss, a University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign doctoral candidate who led the research with professor Catharine Fairbairn. “We found that participants who spent more time looking at themselves during the conversation felt worse after the call, even after controlling for pre-interaction negative mood. And those who were under the influence of alcohol spent more time looking at themselves.”

Professor Catharine Fairbairn’s work focuses on basic social and emotional processes driving alcohol abuse.

The findings add to previous studies suggesting that people who focus more on themselves than on external realities – especially during social interactions – may be susceptible to mood disorders, Ariss said.

“The more self-focused a person is, the more likely they are to report feeling emotions that are consistent with things like anxiety and even depression,” she said.

“Users of the online video call platform Zoom increased 30-fold during the pandemic – burgeoning from 10 million in December 2019 to 300 million by April 2020,” the researchers wrote. “The pandemic has yielded a surge in levels of depression and anxiety and, given reports of heightened self-awareness and ‘fatigue’ during virtual exchange, some have posited a role for virtual interaction in exacerbating such trends.”

In the study, participants answered questions about their emotional status before and after the online conversations. They were instructed to talk about what they liked and disliked about living in the local community during the chats, and to discuss their musical preferences. Participants could see themselves and their conversation partners on a split-screen monitor. Some consumed an alcoholic beverage before talking and others drank a nonalcoholic beverage.

In general, participants stared at their conversation partners on the monitor much more than they looked at themselves, the researchers found. But there were significant differences in the amount of time individual participants spent gazing at themselves.

“The cool thing about virtual social interactions, especially in platforms like Zoom, is that you can simulate the experience of looking in a mirror,” Ariss said. This allows researchers to explore how self-focus influences a host of other factors, she said.

Adding alcohol to the experiment and using eye-tracking technology also allowed the scientists to explore how mild inebriation affected where a person focused their attention.

“In the context of in-person social interactions, there is strong evidence that alcohol acts as a social lubricant among drinkers and has these mood-enhancing properties,” Ariss said. “This did not hold true, however, in the online conversations, where alcohol consumption corresponded to more self-focus and had none of its typical mood-boosting effects.”

“At this point in the pandemic, many of us have come to the realization that virtual interactions just aren’t the same as face-to-face,” Fairbairn said. “A lot of folks are struggling with fatigue and melancholy after a full day of Zoom meetings. Our work suggests the self-view offered in many online video platforms might make those interactions more of a slog than they need to be.”

The National Institutes of Health supported this research.